Pandemic Exacts Heavy Financial Toll on Trucking Companies

[Stay on top of transportation news: Get TTNews in your inbox.]

COVID-19 has delivered a powerful shock to the economy and freight transportation, but the trucking industry will recover — sooner or possibly later — and emerge to face fundamental changes.

To gauge the virus’ impact, Transport Topics surveyed industry experts who offered wide-ranging assessments of the path to recovery, as well the pandemic’s effect on rates, fleet failures and drivers.

Bob Costello, chief economist at American Trucking Associations, described how and why freight markets weakened after an “unbelievably strong” March that helped some fleets capitalize on consumer-related freight while others suffered huge drop-offs.

“This was not an economic crisis,” he said. “It was a health crisis that morphed. We have to get solutions to the health issues for trucking to come out of this completely. Eventually, the economy is going to grow at a really strong clip to historic highs.”

Costello

For now, though, the transportation industry continues to deal with the ripple effects of the pandemic, which has squeezed revenue, earnings and profit margins on freight.

“Everyone is hurting,” said Robert Voltmann, president of the Transportation Intermediaries Association.

A few statistics illustrate COVID-19’s effect on commercial transportation.

The Cass Truckload Linehaul Index showed rates fell in each of the first four months of 2020 at the fastest pace in a decade.

DAT Solutions reported a 19% truckload freight decline from March to April, with spot market rates sinking to their lowest level in three years before recovering in May.

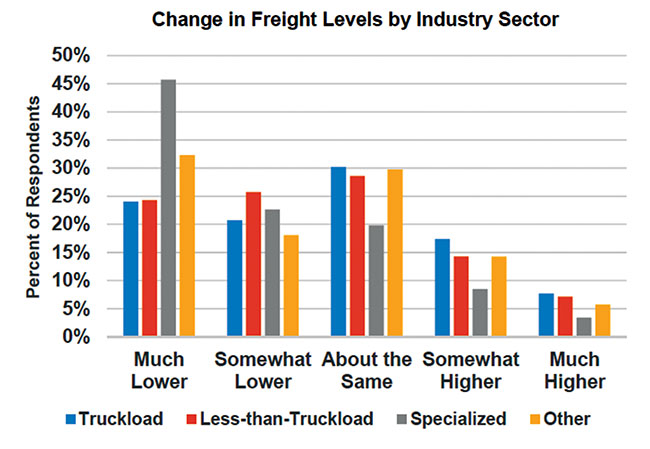

A report by the American Transportation Research Institute and the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association found that nearly half of fleets reported lower volumes.

Asia-U.S. trade lane capacity fell 30% year-over-year in April, said Lars Jensen, president of Danish consultancy Sea- Intelligence, further depressing truck freight.

Economist Noel Perry anticipates the second quarter will be the worst in American history. He projected that U.S. gross domestic product will plummet as much as 30%, on top of the 4.8% GDP decline in the first quarter, reflecting the widespread closures and slowdowns in the services and manufacturing sectors.

Perry

Looking beyond that anticipated trough, industry analysts outlined the prospects for recovery, as well as the forces that will alter freight markets and life in the United States.

Their comments about a future recovery fell into three broad groups: a quick, V-shaped bounceback, a slower recovery possibly stretching into 2021 or beyond, and a pessimistic outlook if the virus cannot be controlled effectively.

“What you hope is that this comes back pretty quickly,” said Perry, whose economic model favors a recovery over two quarters following the multiquarter drop in GDP, which would be the fastest rebound ever if it happens. By comparison, after the Great Recession, it took until 2015 before freight activity and rates returned to the peak levels seen in 2006.

Perry also stressed that the pace of reducing the spread of the contagion is the most important variable going forward.

“If the epidemiologists are right and the economy is closed for six months, that is an unmitigated disaster,” he said.

Donald Broughton, managing partner of Broughton Capital, also foresees a sharp economic recovery.

He noted that COVID-19 triggered a recession based on a self-imposed shutdown rather than an overall economic slump.

“The back half of 2020 is going to be extraordinarily strong,” he said. “We are going to recover. We will get back to business. Mass quarantine was an over- reaction, especially when you look at the extraordinarily low mortality rate and response system throughout Asia.”

ACT Research President Kenny Vieth suggested that trucking could be on the leading edge of the economic recovery.

“For the survivors, things will get better much more quickly than the economy at large. It won’t take much of a turn in economic activity to see some improvement for trucking,” Vieth said, given the expected depth of the second-quarter GDP decline.

Excess freight capacity, which stood at 5% before the pandemic hit, could climb to 16% in the third quarter before rates rebound in the fourth quarter or early 2021 as the economy improves and excess capacity evaporates, Vieth said. Returning to the peak economic levels seen during the fourth quarter of 2019 should take until early 2022, he added.

A recent carrier survey conducted by ATRI and OOIDA provides a breakdown of COVID-19 impact on freight levels.

“There is a lot of room for recovery” since the freight drop-off in the early spring was so steep, said Ken Adamo, DAT’s chief of analytics.

Refrigerated markets in late May matched 2019 rate levels, regaining strength as the produce season coincided with improving overall demand.

However, flatbed freight is a mess, he said, because construction and heavy industry have been shuttered, and fall freight volumes are uncertain as shippers wait to see the scope of the economic rebound before they boost freight levels.

Overall, “Smart people are figuring it out, and preparing for the new normal,” Adamo said. “Shippers have shown the ability to adapt as regional demand shifts. The question is, do we ever return to the old normal?”

Others were more cautious about the timing of the economic rebound.

“I don’t see a realistic scenario for 2020 recovery,” said Jensen of SeaIntelligence.

Even if the virus is gone, and people are upbeat, Jensen believes there are two factors that will slow the process — the unrealistic assumption that all consumers will revert to previous buying habits and the possibility that a second COVID-19 wave would dampen demand. A strong recovery is more likely next year, he said.

It also will take time for supply chains to regain equilibrium.

“What we see every time in downturns is that inventory drops very rapidly,” Jensen said. “When you get to a rebound, you see an extremely sharp increase in volumes that also cause bottleneck issues for equipment and vessels.”

Regardless of the recovery’s pace, experts anticipate some long-term changes in American business, and life in general.

A "Covid kills businesses too" sign is shown outside a store in Salt Lake City. (Associated Press/Rick Bowmer)

Costello and Perry expect that some small businesses won’t recover, and some laid off workers won’t be rehired.

Costello believes COVID-19 accelerated some existing trends, such as reduced business at brick-and-mortar stores. Consumers will come to accept longer home delivery times because they became accustomed to the additional day or two needed to fulfill orders when frenzied buying slowed the supply chain.

TIA’s Voltmann anticipates much more remote work, which could permanently reduce the amount of needed office space. Social situations will be altered until a viable vaccine reduces anxiety. At the same time, he’s certain there is pent-up eagerness to resume all sorts of interactions, including travel and conferences.

Broughton expects the long-term effects of the pandemic to be wide-ranging.

“The most important influence that will emerge will not be the magnitude of the recovery overall, but the widely disparate consequences in each segment of the economy as well as the sociological course changes it will produce,” he said.

He believes Americans will accept safety measures such as having their temperature taken before boarding an aircraft, for example. At the same time, businesses such as restaurants may need larger dining areas and bigger kitchens for safety reasons.

Along the recovery path, some complex situations will have to be addressed.

“Reopening won’t be like turning on a light switch,” Costello said. “Think of an entire wall of light switches that will come on at different stages, with differing magnitude. A factory might want to reopen, but the inputs might come from areas that are still shut down.”

An example he cited was auto plants that need parts from Canada and Mexico that cannot be obtained.

►Essential Work, Truckers Rise to the Challenge

►Top 100 For-Hire Interactive Map

►How the Coronavirus Pandemic Might Reshape Trucking's Future

►Sanitation, Social Distancing Become New Normal in Trucking

Sector Rankings

LTL | TL/Dedicated

Intermodal/Drayage

Motor Vehicle/Driveaway

Tank/Bulk | Air/Expedited

Refrigerated | Flatbed/HS

Package/Courier | Mail

Household Goods/Commercial

“Factories may be able to only run one shift, not to mention demand might not be there. There will be only limited capacity at restaurants,” he said. “While for economic livelihoods these things aren’t great, the smart way is to go back slowly, bring back activity back slowly, and maybe, just maybe, it’s sustainable.”

Vieth focused on how to bring back commercial and personal vehicle production as well as industries such as energy that are freight intensive.

Vehicle manufacturing plants and more than 1,000 major suppliers will have to be synchronized and reopened with new sanitary conditions and fewer employees. Challenges such as finding the necessary cash to support reopening and addressing childcare needs for two-earner families also must be tackled.

“The good news is that we’re a country and an industry full of smart people who will get this figured out,” Vieth said.

Internationally, some freight is stranded at warehouses in loaded containers because retailers are closed, Jensen said. Inability to unload those boxes reduces the availability of empties that U.S. exporters need, disrupting those markets, too. Because those conditions are occurring worldwide, ocean carriers face a widespread, structural imbalance of cargo flows that has not happened before.

“Carriers typically spend $10 billion a year moving empties,” Jensen said. “Now, nobody has the slightest idea of how great the imbalance is, but they need to know that everywhere to be sure to get empties to the right place.”

Meanwhile, freight rates have dropped amid the pandemic.

“Everyone wants rates to go up. Rates are as low as they can possibly be right now,” Voltmann said, referring to early May levels. “Too little freight is chasing too much capacity. A market pickup will benefit all, with improved margins.”

Adamo believes short-term volume, rates and margins will improve in the summer as restaurants reopen and restock and delayed moves of spring home products pick up.

Costello said shippers have been pushing for lower rates as their busi- nesses are squeezed, while dividing freight among more carriers.

Shippers don’t want to sign long-term deals in today’s uncertain rate climate because of the tension between paying rates that keep carriers afloat and the need to match cost savings to their own products’ sale prices, Adamo said.

Late 2020 rates are uncertain because of questions such as how quickly and to what extent demand will return, but the long-term rate picture is favorable, he added.

One fact is certain.

“Nobody can afford to run at these prices, long term,” Adamo said, referring to April rates, though it still makes sense for fleets to keep running as long as revenue exceeds variable cost.

Some trucking companies, however, may not survive the weak market conditions.

April's monthly decline in #tonnage was the largest in 26 years, showing just how much trucking has been impacted by the national response to #COVID19. — American Trucking (@TRUCKINGdotORG) May 19, 2020

Broughton, who has tracked fleet failures for more than two decades, believes they could double in mid-2020 compared with first-quarter levels that already were elevated above 2019. More than 10,000 trucks came off the road in this year’s first quarter, twice the total in 2019’s comparable period.

“We are already seeing significant increases in failures, but they will be nowhere near the levels reached in 2007, 2008 and 2009,” Broughton said.

During the Great Recession, more than 40,000 trucks stopped running in multiple quarters.

The failure pace will be tempered by effective options to manage cash, Broughton said, such as not running at money-losing rates during a brief downturn, and having easier access to factoring.

Costello and Broughton said flexible equipment financing and small business loans also could help fleets survive.

“There will be a round of business failures that will take out incremental capacity,” Vieth said. “A lot of small truckers could fall by the wayside.”

Vieth said some fleets survived the last recession by cannibalizing equipment, which could happen again.

COVID-19 is taking a toll on drivers too, Costello said, though their heroic efforts to keep shelves stocked with essential goods during the pandemic have earned well-deserved publicity and recognition nationwide.

Want more news? Listen to today's daily briefing:

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Alexa | Google Assistant | More