Ducted Fuel Injection Shows Promise for Diesel

[Stay on top of transportation news: Get TTNews in your inbox.]

Researchers have developed a promising yet surprisingly simple modification to diesel engines that could hold the key to reducing the complexity, maintenance, and size and weight of emission aftertreatment systems.

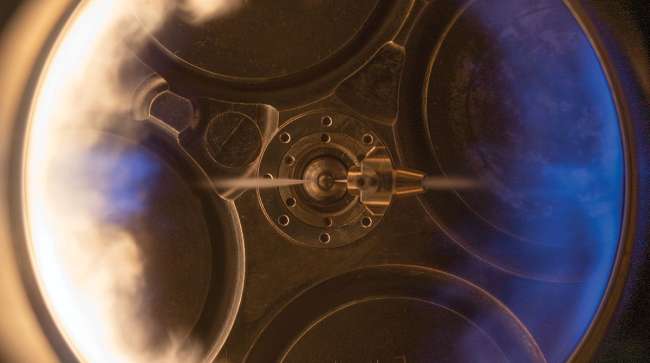

Charles Mueller and three associates at Sandia National Laboratory’s Combustion Research Facility have worked on this modification, called ducted fuel injection, or DFI, that is based on the simple principle of a Bunsen burner, yet has the potential to alter the way we look at diesel combustion and lessen many of the limitations of present diesels.

Since the advent of exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) in 2002, changes to diesel engine design have created more challenges for maintenance while increasing a tractor’s cost.

Sandia National Laboratory

DFI could turn the corner on the tendency of diesel emission technology to grow more costly while mitigating maintenance issues and significantly reducing the size and weight of aftertreatment systems. More specifically, researchers say DFI could reduce diesel exhaust fluid usage, and the tendency for diesel particulate filters to clog with soot and need regeneration. In addition, it may even lengthen oil change intervals by reducing soot loading of the oil, according to Mueller.

Injectors in a traditional diesel engine create rich mixtures in limited areas of the combustion chamber. These areas contain two to 10 times more fuel than is needed for complete combustion, Mueller said.

“When you have that much excess fuel at high temperature, you tend to produce a lot of soot,” he said. “Installing the ducts enables us to achieve diesel combustion that forms little to no soot, because the mixtures contain less fuel.”

He explained the ducts are small tubes mounted a short distance from where the spray of fuel leaves each orifice in the injector’s nozzle. They are mounted to the underside of the cylinder head near the injector nozzle. Mueller believes they ultimately will be made of a high-temperature alloy to withstand the heat of combustion in “production applications with sustained high in-cylinder temperatures.” He believes the incremental cost will be small.

Each tubular duct surrounds and guides its spray for a short distance. The tube’s diameter exceeds the initial diameter of the spray, but because the spray is expanding, it may touch the wall of the tube before it is expelled. Mueller said the tubes do a better job of mixing the fuel with air because they likely enhance the amount of air “entrained” or dragged into the spray, while producing “faster fuel/charge gas mixing down the length of the duct.”

Charge gas refers to intake air mixed with recirculated exhaust. The spray is cooler, and it’s moving faster than normal as it leaves the duct, and this also gives it more time to mix before it ignites, all of which leans out the mixture, he said.

Once the combustion system produces much less soot, it opens the door to using more of what Mueller called “dilution,” or EGR, to lower NOx. “I would expect DFI to be used with significant levels of EGR for simultaneous, cost-effective soot and NOx control,” he said.

This can reduce engine-out soot and NOx to as little as one-tenth of present levels, which has the byproduct of reduction of DEF consumption, he added.

There is a probability, Mueller noted, that the concept will help with net emissions of CO2 and other global warming substances.

“DFI doesn’t produce an appreciable reduction in fuel consumption [in the engine itself],” he said, “but it could provide an appreciable benefit in terms of fuel economy and related costs by lowering powertrain mass, volume, backpressure, and regeneration frequency due to aftertreatment, and total fluid consumption.”

Mueller added that ducted fuel injection works great with conventional diesel fuel, but it works even better with oxygenated fuels, and many renewable, sustainable fuels are oxygenated.

“Soot is second only to carbon dioxide as a chemical that forces climate change, as well as being toxic,” he said.

Mueller said a broad range of engine manufacturers have expressed considerable interest in DFI, and he believes it will be viewed as a “must-have” technology by the industry.

Want more news? Listen to today's daily briefing:

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Alexa | Google Assistant | More