More Fleets Request Downsped Engines, Driven by Fuel Savings, GHG Regulations

Faster isn’t always better, at least when it comes to over-the-road truck engines.

Manufacturers said more fleets are requesting downsped engines that run at about 1,100 rpm at highway speeds, significantly slower than previous generations of diesels. That trend, driven by fleets’ desire to save money on fuel and by federal greenhouse-gas emission regulations, has been made possible by automated engines, faster rear-axle ratios and other improvements.

Aaron Peterson, chief performance engineer at International Truck, said 50% of International Truck’s over-the-road, line-haul tractors sold this year featured downsped configurations, up from 40% the year before.

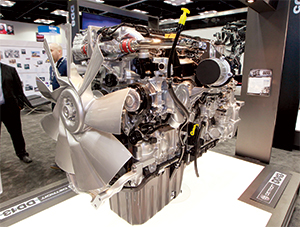

A Detroit DD13 engine. Manufacturers are incentivized to sell downsped engines under the federal greenhouse gas rules. (John Sommers II for Transport Topics)

Downsped engines could grow to 60% to 70% of sales in a few years, he predicted.

Adding a downspeeding package adds about $500 to the cost of a truck, according to the North American Council for Freight Efficiency’s most recent “confidence report” on downspeeding. For many fleets, that’s a bargain. A general rule of thumb for downspeeding is that each reduction of 100 rpm equals a 1% improvement in fuel economy.

Peterson said International has offered trucks with engines running as low as 1,100 rpm, but he doesn’t see it going much lower in the future.

“Gravity isn’t changing, so it still takes a certain amount of power to push a truck,” Peterson said. “It takes 400 horsepower to push an 80,000-pound load up a 1% grade. So if you don’t have sufficient horsepower to do that, then you’re not able to generate at those low engine speeds, then you slow down.”

Other manufacturers also have seen rapid growth in downsped applications.

When independent engine maker Cummins Inc. introduced its version in 2013, sales were in the single digits, said Jason Owens, customer relations manager. Now sales are in the 40% to 45% range for linehaul applications, he said.

Landon Sproull, vice president of powertrain at Paccar, estimated that specs of the downsped powertrain for Peterbilt and Kenworth engines is four times what it was three years ago.

More than a third of Volvo Trucks North America’s on-highway trucks built in 2017 had downsped packages, said John Moore, the company’s product marketing manager for powertrain.

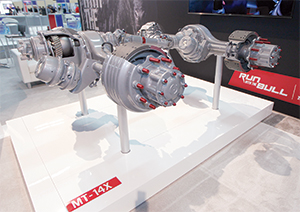

A Meritor axle. The company is testing rear-axle ratios faster than 2:1. (John Sommers II for Transport Topics)

Brian Daniels, manager for Detroit powertrain and component marketing, said sales continue to grow “beyond early expectations.” Detroit is a business unit of Daimler Trucks North America, which builds Freightliner and Western Star trucks.

At component supplier Meritor Inc., sales of faster rear axles, which accompany downsped applications, have grown 26% compared with 2017, said Dawn Clegg, director of product strategy for axles in North America. Many fleets are trying the faster axle ratios for the first time, Clegg said.

Downspeeding has been most prevalent in linehaul applications where trucks stay in high gear on the interstate, but it also can work in applications similar to linehaul, such as transit and regional and vocational cycles, Cummins’ Owens said.

In fact, Cummins is selling downsped vehicles in those types of applications, with the next expansion expected in regional hauls. Some fleets are experimenting with downspeeding while other “cutting-edge” fleets already have moved in that direction, Owens said.

Peterson agreed that downsped engines can be effective in other applications. Some of its less-than-truckload customers have purchased the packages.

“These downsped drivetrains have proven to be very versatile,” he said. “They aren’t just a linehaul application packaging. We’ve brought some versatility into that package so that we can use it for the bulk tank hauls and flatbed applications,” among others, he said.

Driver comfort is a major concern for fleets considering their engine options, particularly in the midst of the driver shortage.

A slower engine has less power on grades, which can increase noise, vibration and harshness. As Peterson pointed out, “It’s very frustrating to be in the seat of one of those trucks that’s losing speed constantly on hills.”

A downsped engine can be quieter as it runs, which can be a plus or minus depending on the driver.

Tony Morthland says Nussbaum Transportation runs downsped engines in all of its 377 trucks. (Nussbaum Transportation)

When Nussbaum Transportation adopted downspeeding wholesale, some of the fleet’s older drivers weren’t accustomed to the quieter noise and grumbled about it, said Tony Morthland, the company’s director of maintenance. For younger drivers, it wasn’t a problem.

Nussbaum now runs downsped engines in all of its 377 trucks and seeks to reduce rpm “as low as anybody will go,” Morthland said. The carrier has seen improvements in its fuel mileage year to year, but it’s difficult to tell how much of that can be attributed to downspeeding.

Meanwhile, truck and engine manufacturers must take steps to meet the Phase 2 greenhouse-gas emission standards implemented by the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Those tighter standards, which will require improvements to fuel economy, begin to take effect in 2021-27 for heavy-duty trucks.

The GHG standards give manufacturers an incentive to produce and sell downsped engines, said Glen Kedzie, vice president and energy and environmental counsel at American Trucking Associations. While downspeeding isn’t mandatory, it can be part of a package that helps manufacturers comply, he said.

As for engine rpm, Alex Stucky, global product strategy manager at Eaton, said over the next three or four years it will creep down to the mid-1,000s. Some fleets request speeds as little as 25 rpm slower as test cases or in large orders.

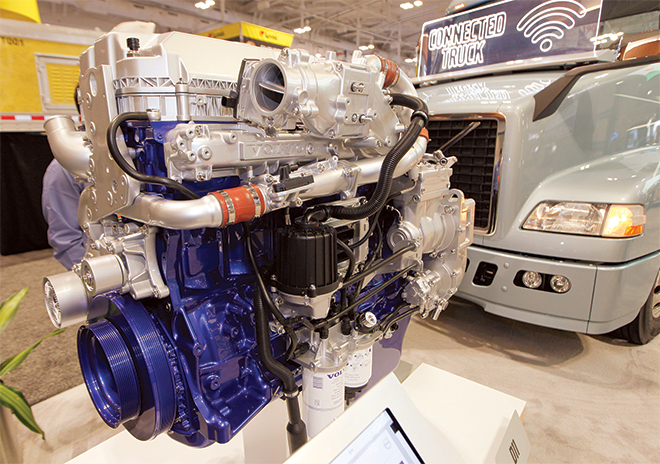

A Volvo engine. The OEM sells a package with a cruise speed as slow as 1,069 rpm. (John Sommers II for Transport Topics)

“It’s an easy thing to spec when they’re ordering a truck that gives them kind of an instant return on investment, so we’ve seen big fleets that are pushing even beyond what we would like to approve from a downsped specification,” Stucky said.

Ultimately, manufacturers can only sell what the market is buying, and what the market wants most is to save money on fuel.

“I think it’s from both directions, but I think at the end of the day, fleet customers are going to be driving the demand on what vehicle spec meets their needs,” Stucky said.

Eaton Cummins’ Endurant 12-speed transmission, launched in October, has been engineered for both current and future applications and can cruise at 1,000 rpm with downshift points at 900 rpm. Stucky doesn’t see cruise rpm at 65 mph falling much below 1,050 rpm.

Paccar’s Sproull said his company isn’t selling any Kenworths or Peterbilts slower than 1,100 rpm, though in Europe a model runs at 900 rpm because trucks travel at less than 55 mph there.

The manufacturer intends to continue its push toward lower engine speeds and will be able to reach 1,000 rpm, Sproull said. But looking ahead three to five years, “I don’t see a path forward in the near future going below 900,” he said.

Cummins’ downsped packages run at 1,100 to 1,140 rpm. The technology will eventually allow slower speeds, Owens said.

“I don’t think a thousand rpm is the floor,” he said. “It’s not much less than that, but I wouldn’t put 1,000 as the floor.”

Volvo, which introduced the technology to the American market in 2011, sells a package as slow as 1,069 rpm cruise speed. In the 1970s, those speeds were almost 2,000 rpm, said Moore. He agreed with several others that speeds can’t go much slower.

“We are getting pretty close to the floor now,” he said. “These engines idle at 600 rpm and we can run 65 miles per hour at 1,069. Downspeeding has come a long way.”

Slowing down the engine requires overcoming challenges.

NACFE’s most recent downspeeding report said an engine cruising at 1,125 rpm increases driveline torque 29% compared with one cruising at 1,450 rpm.

To address that issue, manufacturers continue to reduce the rear-axle ratio. As is the case with rpm, it’s a race to the bottom.

At Cummins, for example, the ratio is about 2.26:1 on a direct drive transmission.

Meritor’s Clegg said the company is testing ratios faster than 2:1, though none are in production at this point.

Tom Bosler, global director of product planning at Dana Holding Corp., said the supplier offers a rear axle ratio of 2.26:1. Reaching 2:1 is “just around the corner in the next year, I would say,” he said.

Bosler and Steve Slesinski, Dana’s director of product planning for the commercial vehicle market, said bringing that number down requires bigger bearings in the axle system, bigger pinion shafts and a draft shaft that doesn’t cause vibration and will hold up during starts and when loading.

At Detroit, “A few years ago, we may have said that a 2.28 ratio was the floor, but as our engineering team continues to innovate and reset what we know as the norm, and now that we can go to a 2.16 ratio, we have not yet found that limit,” Daniels said.