Managing Editor, Features and Multimedia

GHG Proposal Generates Optimism, Caution

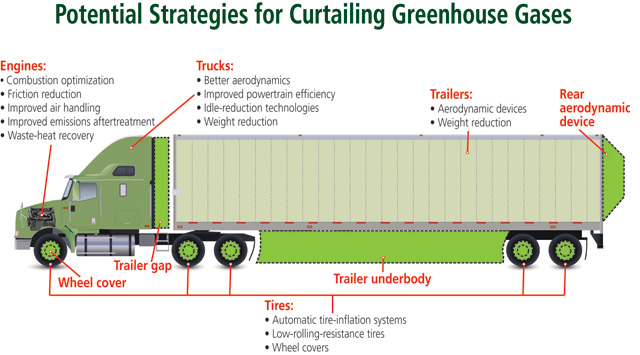

Enhanced aerodynamics, low-rolling-resistance tires, improved powertrain efficiency and waste-heat recovery systems are among the technologies that equipment manufacturers could use to get better fuel economy over the next 12 years, federal regulators said in their proposed Phase 2 greenhouse-gas rule.

Truck and engine makers, however, have had little to say thus far about the specific technology paths they would take to meet the proposed targets.

Last week, manufacturers said they still were busy examining and interpreting the lengthy documents issued by the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, including the 1,329-page main proposal and a 971-page regulatory impact analysis.

EPA and NHTSA said their Phase 2 heavy-truck standards likely would require manufacturers to use both current and emerging technologies, representing a more “technology-forcing approach” than did the Phase 1 standards that began in 2014.

While there is no “silver bullet” to hit the proposed GHG targets, manufacturers can achieve reductions through a combination of engine, vehicle system and operational technologies, the two agencies said in their analysis.

Truck makers could meet the tighter standards through a variety of enhancements, including smoother synchronization from engine to transmission to axles, greater aerodynamics and extended idle-reduction technologies, the agencies said.

They also said engine makers could work on combustion optimization, improved air handling, internal friction reduction, better aftertreatment systems and waste-heat recovery.

“Our initial review has found [the proposal] builds upon the successful foundation of Phase 1,” said Brian Mormino, executive director of environmental strategy and compliance at Cummins Inc., adding that the company is confident it will be able to meet the proposed standards.

For trailer manufacturers, the government listed aerodynamic devices, automatic tire-inflation systems and weight reduction as suggested strategies to boost fuel economy.

The agencies also pointed to low-rolling-resistance tires as an option for truck and trailer compliance.

For existing technologies and those in the final stages of development, EPA and NHTSA projected that manufacturers would apply them to nearly all vehicles, except in applications that would prevent them from functioning properly.

Advanced technologies, such as hybrids and waste-heat recovery systems, also could represent a pathway to compliance, the agencies said.

Waste-heat recovery offers “great promise” as a fuel-saving technology in the long term, but it would take several years to develop and initially would be limited to linehaul applications, the regulators said.

Waste-heat recovery is not commercially available for diesel engines, but prototypes harness exhaust heat generated by combustion to vaporize a fluid and power a turbine to create mechanical or electrical power. The spent gas then gets condensed to a liquid for a new cycle.

EPA and NHTSA said they believe it is “likely” that waste-heat recovery capable of cutting fuel consumption by more than 3% could become available in the 2021-2024 timeframe, but its cost and complexity may limit adoption at that stage.

The agencies projected that waste heat could be used on 1% of all tractor engines in 2021, on 5% in 2024 and 15% by 2027.

Steve Tam, vice president at ACT Research Co., said EPA and NHTSA appear to have scaled down previous expectations on how much waste-heat recovery could contribute to improved fuel economy during the Phase 2 timeframe. “We’re looking at a fairly limited adoption,” he said.

However, if and when waste-heat recovery does become a necessary element for new trucks, it could increase the probability of another “pre-buy” event ahead of that standard, Tam said. That’s what happened in 2006, when truck sales soared to record levels and then plummeted through 2009 as fleets sought to avoid vehicles with added emission-reduction technology introduced in 2007.

“You’re introducing an unproven technology. The uncertainty that that would drive — and potentially the cost associated with it — could set us up for something like a repeat of that pre-buy,” Tam said.

That scenario appears less likely, based on the commentary in the proposal and the low anticipated adoption rates for waste-heat recovery.

The document largely points to more of the same technologies offered now, such as more aerodynamics, more weight reduction and reduced rolling resistance, Tam said.

The proposal would retain EPA’s program that allows credits to be averaged, banked or traded. Manufacturers generate credits by beating standards, and they can use them to smooth out problems.