Senior Reporter

Wreath-Laying Holds Multiple Meanings for Georgia Truckers

[Stay on top of transportation news: Get TTNews in your inbox.]

ARLINGTON, Va. — Husband-and-wife truck driving team Ron and Lea Eppich of Calhoun, Ga., came to Arlington National Cemetery with a truckload of wreaths on Wreaths Across America Day on Dec. 16. The proud trucking couple with Mohawk Industries delivers wreaths to Arlington every year from Maine.

They came to pay tribute to their son, Sgt. Robert Eppich, who served nearly eight years in the Army, did deployments to Egypt, Smeouth Korea, Iraq and Afghanistan, but who died at age 25 on Dec. 19, 2006, in an automobile accident in Texas just three days after returning to the U.S. from a deployment to Iraq.

They have been married 50 years. Ron, a Vietnam-era veteran, served in the Philippines and has been a truck driver since 1979. Lea joined him on the road more than 25 years ago. She proudly says she “drives the night shift” and enjoys the time on the road with Ron.

But in addition to honoring their highly decorated son and paying respects to other Gold Star families at Arlington, this year had additional significance. They came to place a wreath on the grave of Medal of Honor recipient Isaiah Mays, whose story the couple feared could have been lost to history.

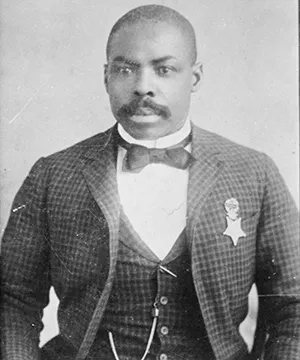

Medal of Honor recipient Isaiah Mays is interred at Arlington National Cemetery. (Library of Congress)

Born into slavery in Carters Bridge, Va., in February 1858, three years before the Civil War, Mays was serving as a buffalo soldier in the Army as a corporal on May 11, 1889, when he and other African-American soldiers were ambushed by a convoy of armed men while transporting $28,300 in gold coins. The coins were part of a payroll being moved throughout the Arizona Territory.

Buffalo soldiers were members of an Army regiment primarily composed of African-Americans, formed during the 19th century to serve on the American frontier.

During the ambush, Mays led his outgunned 12-member infantry team against the bandits and later crawled 2 miles to bring back reinforcements. He and the other soldiers were then in a position where they could re-engage with the thieves, who now had the 250-pound solid oak lockbox.

The thieves managed to flee, but Mays is credited with bravery under fire and because of his courage, while most of the soldiers were wounded, none of them died during this confrontation.

A post-incident report from a U.S. Marshal said, “I never witnessed better courage or better fighting than shown by these soldiers, on May 11, 1889. I am satisfied a braver or better defense could not have been made under like circumstances, and to have remained longer would have proven a useless sacrifice of life without a vestige of hope to succeed.”

Graves of fallen soldiers are adorned with wreaths at Arlington National Cemetery. (Dan Ronan/Transport Topics)

Less than a year later Mays and another soldier, Sgt. Benjamin Brown, were awarded the Medal of Honor. Mays’ citation read, “Gallantry in the fight between Paymaster Wham’s escort and robbers. Mays walked and crawled two miles to a ranch for help.”

Three years before his death, Mays sought a military pension, but he was denied the funds on a technicality. In 1925 he died at age 67 in an Arizona state-run hospital for people who had tuberculosis and those living in poverty. He was buried in the hospital cemetery with a small headstone with only a number on it, and no mention of his military service and bravery.

In 2009, the Old Guard Riders — a nonprofit military and veterans group that the Eppichs helped create — heard about Mays’ story. They went to court to get Mays’ remains disinterred, cremated and then brought to Arlington National Cemetery for a burial ceremony befitting a Medal of Honor recipient.

A woman lays a wreath on a grave. (Dan Ronan/Transport Topics)

“We started a nonprofit, a 501(c)(3) organization after Robert died, to get indigent veterans interred at the national cemeteries,” Lea said. “We wanted them to have some dignity.”

“We helped bring Isaiah Mays to Arlington and today we are laying a wreath on his grave,” Ron said. “It’s wonderful to see these people out there and this is our way to give back.”

A few minutes later, Ron and Lea walked hand in hand across the vast burial ground to the old section of Arlington National Cemetery and quietly laid a wreath on Mays’ grave. They paused for a moment and said his name out loud, then went back to their truck and spent the day at their trailer handing out thousands of wreaths to volunteers.

“Sometimes the easiest way to deal with your own grief is to help others deal with their grief,” Ron said.

Now and forever, Mays is back in his home state of Virginia, along with the tens of thousands of other military heroes honored that day.

“This is our way of including our son and all the veterans, because this is the time of year we miss our son and all of them the most,” Lea said, her voice cracking with emotion.

Want more news? Listen to today's daily briefing below or go here for more info: