Bloomberg News

Truck Driver Shortage Sets U.K. on Path for Food Chaos

[Stay on top of transportation news: Get TTNews in your inbox.]

The United Kingdom is running out of time to find more truck drivers before isolated incidents at supermarkets and fast-food chains erupt into a deeper crisis that leaves businesses crippled by delivery delays and shortages.

Despite the mounting risks, there’s a standoff between the government and businesses about a solution. Meanwhile, consumers can’t get milkshakes at U.K. branches of McDonald’s Corp., some stores are running low on bacon, milk and bread, and there have been warnings of shortages at Christmas.

On top of that, the logistical squeeze could push up costs for businesses, which means higher prices for customers. That would feed an inflation rebound that’s already getting juiced by higher costs for oil, crops and metals.

“I don’t want to scaremonger and there is no need to panic-buy, but that said, availability has never really been so bad,” said Richard Walker, managing director of supermarket chain Iceland Foods. “It’s getting worse and you can see that when you go into the shops.”

The intense scramble to get products — from fresh food to car parts — is playing out around the world as a post-lockdown surge in global demand fuses with supply squeezes, worker shortages and port disruption to create chaos in well-honed processes once taken for granted.

But the drama in the U.K. has the added twist of Brexit, which is complicating hiring from the European Union. The industry strains and warnings of empty supermarkets, even if exaggerated, have added more fuel to the bitter debate over the divorce.

As hauliers and retailers adapt to address some of the headline-grabbing shortages, they’re also pushing for government help. They want EU truck drivers added to a special visa program to make it easier to fill the estimated 100,000 shortfall in workers, but the government is refusing to budge, arguing that companies can lure staff with better wages. Businesses say hiring and training will take time, and there’s a pool of skilled drivers on the European continent that can be tapped much faster.

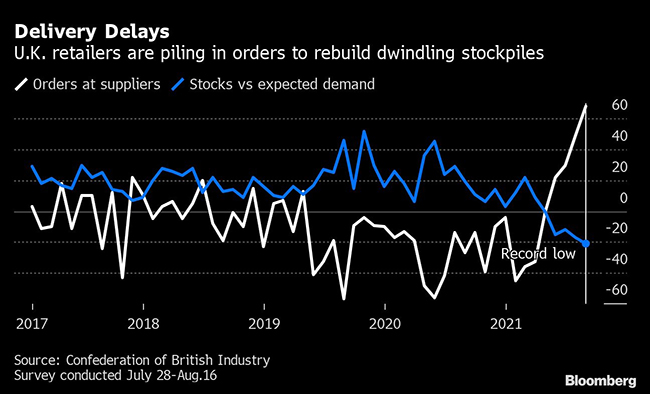

Companies are desperate for a fix as the Christmas clock is ticking. Stores need to start stockpiling for the peak period, but that’s proving impossible as they deploy limited delivery capacity just to keep food on shelves now.

A number of larger retailers, such as Wm Morrison Supermarkets Plc and Asda, are sending their own trucks direct to suppliers to pick up goods. Many are reducing or suspending penalties for supplier delays, and offering bonuses to attract new drivers. Dixons Carphone Plc, an electronics retailer, is covering the cost of training and tests for employees who want to become heavy goods drivers.

The issue is affecting businesses right across supply chains, which means hurdles at multiple stages in the delivery process. A report Aug. 27 showed that about 7% of U.K. businesses weren’t able to get the goods or services needed from within the U.K. in the previous two weeks, while stock levels at many firms are below normal. According to the British Meat Processors Association, more than half of all job vacancies in the U.K. are in the food and drink sector.

“The government has said there’s enough people in the U.K to fill these jobs,” said David Lindars, operations director at the association. “But where are they hiding? No one knows.”

The Sevington Inland Border Facility near Ashford, U.K., on Aug. 11. (Jason Alden/Bloomberg News)

Concern about the labor squeeze is echoed across companies.

“The problem is not that we don’t have or can’t make the goods, it’s a matter of a shortage of drivers,” said Peder Tuborgh, chief executive of Danish dairy firm Arla Foods, a major supplier of butter and milk in Britain. “The situation is partly caused by Brexit.”

Tesco Plc, one of the U.K.’s biggest supermarket chains, said this week there has been some impact on business, but it remains limited. That said, media stories of missing products and pictures of empty supermarket shelves on social media are taking hold among the public. At worst, they could encourage the type of panic-buying seen in the early days of the pandemic in 2020.

“At the moment, we’re running very hard to keep on top of existing demand and there isn’t the capacity to build stocks,” Chairman John Allan said on BBC radio. “There may be some shortages at Christmas, but I wouldn’t want to over-dramatize the extent.”

Behind the headline-grabbing food issues, other industries are also mired in their own crises. Given the concoction of global and domestic factors — from container shipping to immigration hassle — the supply crisis could be prolonged. With each passing week, complex yet streamlined delivery chains get more and more upended, increasing costs and denting profit margins.

Earlier this week, Gavin Slark, the head of construction products company Grafton Plc, said the pressures are “with us for the rest of this year and certainly going into next year.”

As much as companies can do now to keep trucks moving and customers happy, the pressure is likely to increase. George Shchegolev, co-founder of logistics software company Route4Me, says he’s very busy dealing with firms looking at options for the coming weeks and months.

“Every successful company that I know has been putting a lot of effort into getting ready for this,” Shchegolev said. “The ones that don’t are going to lose a lot of business.”

— With assistance from Morwenna Coniam, Libby Cherry, Christian Wienberg, Kitty Donaldson and Khadija Kothia.

Want more news? Listen to today's daily briefing below or go here for more info: