Senior Reporters

Traffic Woes Underscore Infrastructure Needs

Traffic jam on I-81 by Eric Miller/Transport Topics

Traffic jam on I-81 by Eric Miller/Transport Topics This story appears in the May 15 print edition of Transport Topics.

TOMS BROOK, Va. — On a dreary overcast afternoon this month, a several-miles-long traffic jam was forming quickly on Interstate 81.

Motorists heading northbound were rubbernecking a damaged tractor- trailer resting in a grassy area about 100 yards off the highway. Lights on a state patrol car flashed, a fire truck arrived and a road worker picked up pieces of the wreckage.

Accident-related delays are commonplace on one of the state’s most heavily traveled highways, which also happens to be the main commercial corridor for trucks throughout Appalachia. There were about 2,000 crashes last year on Virginia’s I-81, 22% of them involving trucks, according to the Virginia Department of Transportation.

This one, near mile marker 302 just north of Front Royal, was hardly different.

COMING MAY 19: LiveOnWeb Infrastructure Week Reporter Roundtable

Accidents frequently contribute to a major congestion problem on I-81. Virginia transportation officials have pondered solutions ranging from adding a truck-only lane to widening the portion of the interstate that stretches through the state.

Virginia and Maryland transportation officials are vying for federal grants to expand I-81. U.S. DOT intends to announce the recipients this spring.

Funding is a source of tension for stakeholders, who tend to disagree on how to pay for repairs and modernization projects.

They await President Donald Trump’s long-term infrastructure plan for an answer to the country’s transportation funding problems. With the Highway Trust Fund projected to run low on funds by 2020, state officials claim they are unable to sketch out multiyear projects that require federal dollars.

The I-81 corridor will be among the highways and projects closely examined during Infrastructure Week during May 15-19 in Washington, D.C., and around the country.

The weeklong event features panels, seminars and advocacy meetings on Capitol Hill.

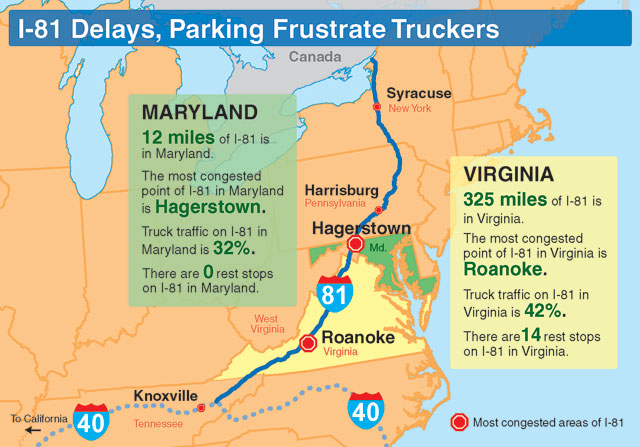

In all, I-81 winds through the eastern part of the United States, from as far north as New York’s border with Canada, and terminates 850 miles southwest in Tennessee. Trucks constituted a large percentage of the vehicles traveling the corridor — reaching as high as 40% of total vehicle traffic in sections between central Pennsylvania and Virginia, according to the I-81 Corridor Coalition. This stretch of the corridor also experiences the highest levels of congestion and the greatest fre- quency of crashes, the group said.

Truckers and transportation observers agree the corridor needs an upgrade.

Bill Stanton, a branch manager for Love’s Travel Stops and Country Stores, said he regards I-81 in Virginia as more of a problem than the coastal I-95, primarily because I-95 has more lanes while I-81 is only two lanes in each direction. Transportation planners have long been discussing an array of potential trucking improvements on I-81, he said.

“They’ve talked about widening the road since I’ve been a child — that’s 30 or 40 years,” Stanton said. “[I-]81 is congested, especially if you have any kind of accident or road construction. It can back up for hours.”

Cheap fuel prices in Virginia are another contributor to congestion, he added.

“You have a lot of state taxes in Maryland, West Virginia and Pennsylvania,” Stanton said. “That makes this a destination for many professional drivers and their companies. Even if you have to go out of your way, it’s still more cost-effective to get cheaper fuel.”

Then there is the parking.

“With 81 being one of the busier interstates, you’re going to have parking problems,” Stanton said. “Those guys have to get off the road after a certain amount of time, and we don’t have enough rest areas. If you drive 81, you see every rest area is packed.”

While the interstate offers some of the nation’s most picturesque vistas, truckers said its beauty too often is betrayed by a dangerous mix of cars and trucks traveling at high speeds or not fast enough.

Trucks are plentiful on I-81, but that doesn’t mean they can have their own way on the road. Many truckers regard the corridor as an elaborate obstacle course that frequently stands in the way of making timely deliveries, or nibbles away the limited hours the federal government allows them to drive.

Layne by Eric Miller/Transport Topics

Layne by Eric Miller/Transport Topics When traffic is minimal, cars and trucks routinely reach 80 mph, despite a speed limit 10 mph lower. When traffic comes to a standstill in the event of an accident or simply overcrowding, tempers sometimes boil over.

“[I-]81 is a dangerous road for some reason,” Mel, a truck driver for Wal-Mart Stores Inc. who declined to be identified further, told Transport Topics. “It’s a rush, rush attitude, where it’s me, me, me, and I’m more important than you.”

Edison Layne, a Bloomfield, Conn.-based owner-operator, blamed motorists’ bad habits for congestion and accidents.

It is common to find drivers tailgating truckers for several miles, so close at times that truckers are unable to see them in their mirrors, Layne said. He’s also seen cars pass him, pull in front of his truck and slam on the brakes.

Parker by Eric Miller/Transport Topics

Parker by Eric Miller/Transport Topics “The problem is the four-wheelers,” Layne said. “We’ve got a lot of four-wheelers that do a lot of dumb stuff.”

He also blames the congestion on construction zone traffic.

Jim Parker, a driver for Rosedale Transport Inc., of Dalton, Ga., described a need for more truck parking areas.

“A lot of the truck stops don’t have enough parking available. And when you’re out of hours, you can’t just keep on going,” Parker said. “As a driver, I’m on the road and I’m constantly seeing trucks parked on both sides of the highway.”

Dale Bennett, president of the Virginia Trucking Association, acknowledged the corridor’s unique challenges.

Unlike Northern Virginia, where truckers know where to expect congestion points at certain times of the day, the I-81 corridor is much less predictable, he said.

“You have a wreck, and the whole world stops. But you never know when they’re going to occur, or where,” Bennett said.

“Parking is a challenge,” he added. “VDOT did a study and found a deficit of about 890 parking spaces in the whole corridor.”

Trucks travel 1.2 billion miles annually on Virginia’s 325-mile leg of I-81. According to VDOT, about 42% of all truck traffic statewide travels along the corridor. About 48 of those miles have grades greater than 3%, sometimes causing “rolling roadblocks” when one truck passes another, blocking both lanes. But it’s not like Virginia transportation planners aren’t trying to wrestle with the mess.

In December, VDOT submitted a $128 million request for federal grants for projects aimed at improving safety, reliability and operations along the freight corridor. The Trump administration is reviewing applications, and recipients are expected to be announced this spring.

VDOT hopes to use the federal funds to reduce 16 “friction points” on the corridor, improve incident detection and response times and implement a truck parking management system.

In addition, nine state road projects already have been funded for improvements along I-81.

About 70 miles north, truckers also frequently encounter congestion on the short section of I-81 that crosses through western Maryland.

Jim Ward, CEO of D.M. Bowman Inc., a trucking and warehousing firm based in nearby Williamsport, Md., has repeatedly sounded the alarm on the need to expand the corridor.

Traffic on the Maryland stretch of I-81 is not slowing down, nor is the area’s population growth. And that congestion ultimately leads to higher prices for goods.

A way to quickly remedy the traffic flow would be to raise the federal tax on fuels to fund road improvements, Ward said.

“We prefer those dollars that go in through those federal fuel taxes be used for the highways and bridges across our nation to improve the free flow of goods,” Ward told TT.

I-81 runs for 12 miles across western Maryland, serving as a prominent connector with Virginia, West Virginia and Pennsylvania. Trucks are nearly a third of traffic, according to the state’s department of transportation. In Hagerstown, Md., the average daily traffic is approximately 78,520 vehicles with trucks accounting for about a quarter of the total.

Several truckers at the Love’s Travel Stops and Country Stores off Exit 10A in Hagerstown complained about the corridor’s congestion.

“Getting stuck in traffic doesn’t just slow you down, it costs you money,” said Carlos Gonzalez, who was refueling his truck for a trip northbound to Pennsylvania to deliver auto supplies to vendors. He said he’s been a commercial driver for nearly a decade.

Motorists who squeeze in front of trucks are a big reason for the traffic woes, Gonzalez told TT.

“This is a bad area for traffic jams,” he said of I-81’s Maryland stretch. “It gets bad, too, up north.”

Some improvements are underway, however.

The Maryland DOT has begun to widen I-81 between U.S. 11 in West Virginia and the Maryland state Route 63/68 interchange. The target completion for that $105.5 million project is the summer of 2020. West Virginia DOT contributed nearly $40 million. Like Virginia, Maryland’s DOT has applied for a federal freight grant to help pay for the project.

Dozens of current and former transportation officials, members of academia and industry stakeholders have explored ways to improve the corridor for more than a decade through the I-81 Corridor Coalition. Based at Virginia Tech Transportation Institute, the coalition calls on federal lawmakers to boost funding for congestion mitigation and safety improvements.

It also examines ways to enhance the flow of freight when expanding lanes and capacity is not a viable option, said Andy Alden, the coalition’s executive director.

“Adding a third lane is always great for capacity building, but it’s also insanely expensive,” Alden said. “Given the environment we’re working with right now, with the limited funding for these types of things, we really need to do more with what we have instead of building new infrastructure and new capacity.”