Fleet Failures at 2-Year High in Weak 3Q Freight Market

This story appears in the Oct. 17 print edition of Transport Topics.

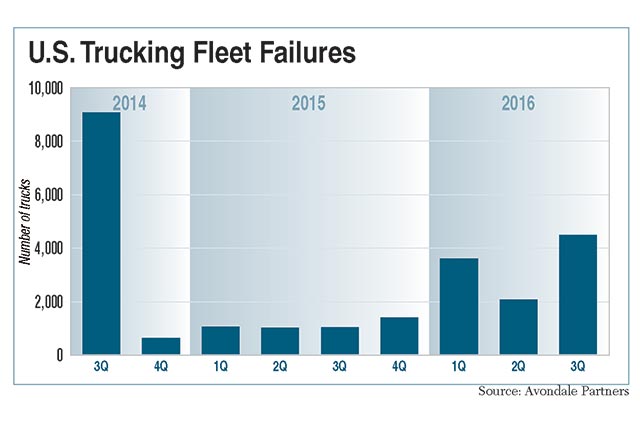

Fleet failures, measured in trucks pulled off the road, spiked in the third quarter to a two-year high, propelled by deteriorating rates, a stagnant freight market and gradually rising diesel prices, according to a new report.

Failures pulled 4,475 trucks off the road in the quarter — more than quadruple the 1,005 in the year-earlier period and more than double the 2,050 in the second quarter — Avondale Partners analyst Donald Broughton told Transport Topics last week. The number of failed businesses totaled 185.

“This is a significant increase, but it is still not a large number on a historical basis,” Broughton said. “The reasons for the increase are simple. Fuel is no longer a benefit. It hasn’t gone up dramatically, but it has gone up a little. Demand is lackluster. Rates have gone negative — in the spot market for a while and now on the contract side.”

The number of failures was the highest since the third quarter of 2014, during which 9,090 trucks were pulled from the road. The relative level during the third quarter this year is illustrated by the fact that the number of trucks in failed fleets during the first nine months barely topped the single-quarter mark in the 2014 period. Failures have been on the rise for four consecutive quarters.

“Failures remain historically low,” said Bob Costello, chief economist at American Trucking Associations, though the number of fleets increased by 54% sequentially. “I think the truck freight market remains challenging, and I’m not surprised by the bump up. Nor would I be shocked if it continues to rise modestly until industry supply and demand come more into balance.”

The flat freight market is illustrated by the fact that loads in the first eight months of 2016 are just 0.2% higher, according to ATA statistics. Meanwhile, rates as measured by the Cass Information/Avondale truckload linehaul index were 2.8% below August 2015, marking the fifth consecutive month when rates trailed last year. On the fuel front, diesel prices rose 11% from the start of the second quarter to the end of the third quarter.

“When rates are down, miles run are down, and fuel costs go up even slightly, there are companies that are running out of cash,” Broughton said. Although failures are on the rise, Broughton believes there is no reason to think that the excess supply of capacity in the market will be dried up anytime soon. In fact, he believes it could be late 2017 before market conditions improve.

“It is very possible that we will continue to see a lackluster environment on the demand side and a negative rate environment,” he said. “Over time, that is enough to kill a trucker.”

Broughton emphasized that fleets go out of business gradually. “The companies that failed were not robust in the first and second quarter and then fell off the cliff in the third quarter,” he said.

“In almost all cases, one of the symptoms is the age of the fleet,” Broughton added. “Fleets are hiring unsafe drivers because they haven’t figured out how to get them the miles. Maintenance is inadequate.

“As they start to run out of cash, they stop investing in the fleet. Then they get to a point of no return, when trucks break down more often and are in the shop more. That makes it harder to retain drivers. Claims costs can go up. The old trucks are worth less, so their ability to borrow against them goes down.”

Another symptom of failure, he said, is measured in revenue per truck per week, excluding fuel surcharge. Those approaching $4,000 on that basis are strong, while those that struggle to reach $3,000 often are in financial difficulty.

Among publicly traded fleets, Covenant Transportation Group has had the highest revenue on that basis both in the first half of 2016 at $3,741 and all of last year at $3,967. Covenant ranks No. 43 on the Transport Topics Top 100 list of the largest for-hire carriers in the United States and Canada.

Broughton added that revenue per truck per week has to be coupled with effective management of costs.

He said the average number of trucks in failed fleets was 24, an increase over past quarters. That was driven by the fact that two companies that operated 300 to 500 trucks were counted in Broughton’s report. One of those companies was a Chicago-area business that pulled about 500 trucks out of over-the-road service but maintained a local pickup-and-delivery service. He declined to identify the other company.