Senior Reporter

Removing Non-Fault Crashes Helps CSA Scores, ATRI Says

A new research report lends support to claims by many in the trucking industry that federal regulators should remove nonpreventable crashes from carriers’ Compliance, Safety, Accountability program records.

The report, issued last week by the American Transportation Research Institute, concludes that removing crashes in which carriers were clearly not at fault would result in significant improvements for the majority of the carriers’ CSA Crash Indicator BASIC percentile scores.

The ATRI analysis used 15 motor carriers’ crash records contained in the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration’s Motor Carrier Management Information System database to identify “a small and noncontroversial subset of nonpreventable crashes.”

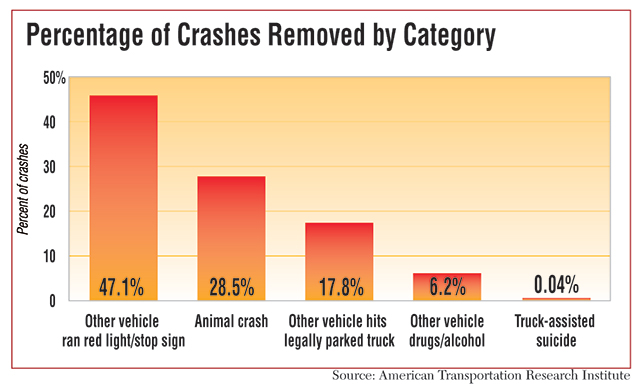

Crashes removed from the carriers’ scores included animal collisions, other vehicles hitting legally parked trucks, other vehicles running a stoplight or stop sign and hitting trucks, crashes in which the operators of the other vehicles were driving under the influence and so-called “truck-assisted suicides,” whereby a despondent person walks in front of a truck.

The analysis removed those crashes and recalculated the score within the Crash Indicator portion — measured by a pattern of high crash involvement, including frequency and severity — of BASIC.

BASIC, or Behavior Analysis and Safety Improvement Categories, is how FMCSA quantifies performance.

“ATRI’s report confirmed the intuitive, that failing to distinguish crash involvement from crash causation results in an inaccurate representation of fleet safety performance,” said Rob Abbott, vice president of safety policy for American Trucking Associations. “Ultimately, the goal of the CSA program should be to identify those fleets most likely to cause crashes — not those more likely to be involved in crashes due to exposure issues like driving in urban areas.”

“The problem is, how do you know which ones are obvious from the ones that aren’t obvious?” Henry Jasny, general counsel for the Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety, said last week. “There are some that everybody could agree on, but that’s probably a small number.”

Jasny added, “And you’re leaving it to an agency that the industry basically says can’t chew gum and walk at the same time.”

FMCSA has studied the issue but concluded in a January report that the agency does not have a foolproof, or affordable, path to follow for quickly assessing fault in crashes and then using those judgments to predict future crash risk among carriers.

FMCSA spokesman Duane DeBruyne said the agency could not comment by press time because it had not yet analyzed the report.

Among the carriers in ATRI’s analysis, the Crash Indicator measurement improved by an average 5.3% when the nonpreventable crash subset was removed.

By not removing the nonpreventable crashes, the agency’s formula “may mislead conclusions about a carrier’s actual safety performance,” ATRI said.

“For example, if a legally parked commercial motor vehicle is struck by another vehicle and qualifies as a DOT-reportable crash, this negatively impacts a carrier’s Crash BASIC measure,” said the study, published Nov. 10.

Such crashes can leave the impression that a carrier is less safe, ATRI said.

“The trucking industry has identified a number of flaws in FMCSA’s calculation of carrier safety performance through the CSA BASICs, and perhaps none is more egregious than the inclusion of nonpreventable crashes in the Crash Indicator BASIC,” Scott Mugno, a member of ATRI’s research advisory committee and vice present of safety and maintenance for FedEx Ground, said in a statement. “ATRI’s latest analysis, using a very conservative definition of nonpreventable crashes, demonstrates just how skewed FMCSA’s BASIC calculations can be.”

ATRI estimated that not including the nonpreventable crashes in the 15 carriers’ safety measurement scores could save them a total of $68 million.

Including nonpreventable crashes in a carrier’s safety profile can create higher insurance costs, legal consequences and lost productivity from more frequent inspections, ATRI said.