Public, Private, Nonprofit Sector Insiders Team to Focus on Nation’s Infrastructure Woes

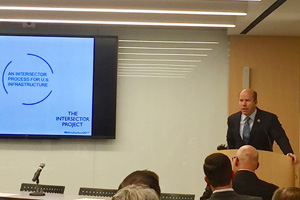

At a post-election, pre-115th Congress event Dec. 13, representatives from all three sectors discussed best practices and examples of successful projects while offering advice to the incoming Trump administration and lawmakers on how to fix the $3.3 trillion infrastructure funding shortfall.

“Few things can be solved in one sector alone,” said Intersector Project Chairman Frank Weil, who also is chairman of private investment firm Abacus and Associates.

Weil noted that the sectors have different cultures and don’t fully understand each other’s, which is why longtime government staffer Peter Peyser said, “This is all about getting us to sing off the same sheet of music.”

Said Rep. John Delaney (D-Md.), the only House member who was the CEO of a publicly traded company, “When the sectors work well together, you get very good economic outcomes … and the quality of life improves.”

Which is why Delaney said a large-scale infrastructure program “should be our top domestic economic priority,” ahead of Trump’s touted tax reform. “The fact that we’ve underinvested in infrastructure [for many years] clearly impacts the day-to-day lives of our citizens,” Delaney said. “And there’s really no better jobs program than an infrastructure program.”

"When the biz, gov & non-profit sectors work well together, you get very good economic outcomes." -@RepJohnDelaney #Infrastructure2017 — Intersector Project (@theintersector) December 13, 2016

Delaney advocated for the creation of a national infrastructure bank and devoting more money to the Highway Trust Fund as well as repatriating much of the $2.5 trillion that American multinational corporations have stashed overseas to avoid domestic taxes.

“We have to seize the opportunity,” Delaney said, referring to still-low borrowing rates and Trump’s boast of a $1 trillion infrastructure program. “It’s incredibly important that we make sure that infrastructure stay[s] as the [federal government’s] top priority. If we do broad-based tax reform, it will be hard to get the kind of infrastructure dollars that … we need.”

In contrast, David Parkhurst, general counsel for the National Governors Association, said tax reform should be “the vehicle” for funding infrastructure because fuel taxes, tax credits and tax-exempt municipal bonds figure to be part of that effort. Several panel participants stressed the importance of maintaining the latter’s status since they fund 75% of American infrastructure projects.

Nick Donohue, Virginia’s deputy secretary of transportation, extolled the fact that no public money will be spent to add managed toll lanes on Interstate 66 outside the Capital Beltway thanks to a partnership with a private sector firm. However, Donohue quickly added that public-private partnerships aren’t the right answer for the majority of infrastructure needs.

“There’s a lot of private capital that is out there and is willing to invest in projects,” Donohue said. “If there’s an 82% tax credit for equity invested [in infrastructure as Trump has suggested], what is the rate of return applied on? Is it applied on the [full] investment or the 18% they didn’t get a tax credit for?”

Donohue added that it would be “very problematic” if such a tax credit program replaced the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act as the federal government’s chief financing arm for large infrastructure projects, an opinion with which Parkhurst strongly agreed.

Sarah Kline of the Bipartisan Policy Center praised the construction of the Port of Miami tunnel project — which was critical in easing the path for goods and tourists to be transported from I-95 to the port a mile across Biscayne Bay — for eschewing tolls in favor of availability payments, in which private investors only get fully paid if the assets they construct maintain certain performance standards.

“This is a model that some public-private partnerships are starting to use in cases where the infrastructure project doesn’t generate its own revenues,” Kline explained.

Brian Pallasch, managing director of the American Society of Civil Engineers, focused on the costs of inaction: $7 trillion in lost business sales by 2025; 2.5 million jobs at risk; and $3,400 to the average family per year or $9 per day.

“Sometimes we fail to remember that we’re already paying for infrastructure every day,” Pallasch said. “If we invested more [in infrastructure], we’d have more [money] in our pocket[s].”