Education, Outreach Programs Seen as Front Lines for Attracting Next Generation of Truck Technicians

When Jeff Harris, vice president of maintenance at USA Truck Inc., first started as an apprentice truck mechanic 29 years ago, he had a trade school diploma, a basic set of tools, a couple of crusty old mechanics who took him under their wing and showed him the ropes, and a desire to learn.

“I’ve always been a gear head, pretty good at turning a wrench and always liked the challenge of figuring out what was wrong with something and fixing it,” said Harris, who also serves as chairman of the Technology & Maintenance Council, a council of American Trucking Associations.

Harris addresses the crowd at 2018 TMC after becoming chairman.

(John Sommers II for Transport Topics)

That was then. Today, having a mechanical aptitude, being good at working with your hands and possessing an intellectual curiosity about how to fix something remains important. What’s dramatically different, however, is the path to becoming a diesel technician, as well as the job itself, the education needed and the skills required.

Harris has seen that change firsthand, through the experience of his 18-year-old son, who is in USA Truck’s diesel technician apprenticeship program. The younger Harris’s path to certification will require far more time acquiring and applying computer skills, learning about complex computer diagnostics software, learning to read schematics, understanding fault codes and troubleshooting a myriad of electronic control systems, than learning how to lube a chassis or change out brake pads. Although fundamental mechanical skills remain a core foundation, the job has become much more technology-oriented.

And unlike an old-school, book-based, “in the classroom, teacher at the chalkboard” education, his training is more interactive. It’s in a hands-on shop environment, with skills demonstrated live by senior techs as instructors, or through web-based sessions, and reinforced through adaptive, computer-based online learning tools — some of which resemble the workings and progressive learning steps of sophisticated video games.

That old 4-inch-thick, hard-bound Chilton repair manual? It’s nowhere to be found — replaced by an iPad and a smartphone.

A study released last year by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projected that from 2016 to 2026, there will be 283,000 openings for service technicians in the automotive and commercial-truck maintenance and repair fields. Of those, 10% were classified specifically as “truck and bus mechanics and diesel engine specialists.”

Patrick Pendergast, vice president of talent acquisition for truck-leasing and maintenance provider Ryder System Inc., thinks that estimate might be low. In his view, the industry today is barely filling the openings left by baby-boomer technicians who are retiring — much less meeting the demand for new techs. Ryder operates from 800 locations and employs 5,900 maintenance technicians.

If the industry is to successfully fill the talent gap, fleets and truck centers, truck manufacturers, community colleges and technical schools, educational accreditation and industry associations collectively must find new and better ways to attract more people into the field, improve and accelerate the training process, and make learning more interesting and interactive, Pendergast said.

How does Ryder address that challenge? For one, the company has “a strong partnership with the military,” Pendergast said. “We are recruiting and training exiting military on-base, before they separate. We engage with those coming out of the service, and give them training so when they get home, they can hit the ground running,” he said, adding that qualified candidates have a job offer before they leave the military.

Ryder’s program is up and running at two U.S. military bases, with plans to expand to four more bases. The company, similar to other fleets, dealers, truck repair centers and truck builders, also partners with and supports community colleges and technical trade schools across the country.

Local Ryder maintenance managers sit on advisory boards and provide input on the curriculum. Equipment is donated for hands-on training. The company sponsors skills competitions, offers internships and tuition reimbursement, and provides loans to help budding technicians buy tools. A scholarship program awards grants to high-achieving, high-potential students.

Ryder also recognizes and rewards its top-performing truck maintenance technicians in the annual Ryder Top Tech Recognition program for North America. Last year, 1,800 of Ryder’s 5,900 technicians competed for honors and cash prizes.

Pendergast and his team also work with the National Association of Trade and Technical Schools, the accrediting body for vocational and trade schools, as well as TMC, to develop training standards, curricula, tools and best practices, and to promote careers in the field.

A technician’s job “is an entry point, and for those who want it, a fulfilling career path that can lead to management, leadership and running big pieces of a business,” Pendergast said.

Tim Spurlock, president and co-founder of American Diesel Training Centers, based in Columbus, Ohio, said one challenge is that vo-tech jobs aren’t considered “cool” by many 18- to 26-year-olds. Yet most of those who don’t go to college end up in “low-skill, high-effort jobs,” such as landscaping, warehousing, retail or other nonskilled labor with no career path. Or they are driving for Uber or Lyft.

The biggest barriers to a technical training school for this demographic: time and money.

They’re already working. They don’t have the time or financial resources to fund the tuition for a traditional, six-to-eight hour per day, one- or two-year technical school, Spurlock said. “We have to adapt to their situation.”

American Diesel’s program is 12 weeks, with 90% of the training being hands-on. Classes are five hours a day, so students, if they choose, can continue earning a living wage in another job. Other curricula is delivered through an American Diesel-designed online adaptive learning platform, he said.

American Diesel Training Centers

The school also participated in a TMC-led task force last year that defined what areas were required for an entry-level technician. The 130-company survey narrowed the list down to 420 core tasks.

“That’s what we teach to,” Spurlock said. The platform’s algorithms “learn” with the students, speeding them through subjects in which they quickly demonstrate proficiency, or slowing down and spending more time with them on subjects with which they struggle. The online learning system then tracks and rates student progress and proficiency in completing lessons associated with each task.

The software design also has elements of “gamification” with formats, tools and learning processes mirroring the functioning of video games that today’s millennial generation is comfortable with.

The average age of an American Diesel student is 25. Graduates typically enter an entry-level job or an apprenticeship. It works with Kenworth, Penske, Love’s Travel Stops, J.B. Hunt and Ryder, among others, to place its graduates.

Meanwhile, as the cost of a traditional college education has skyrocketed, more high school students — and their parents — are questioning the investment in, and ultimate return from, a four-year degree. That’s driving more interest and opportunity for technical trade schools, which can offer a faster path to a solid income and a rewarding vocation.

The demand is certainly there. In January, 12,914 diesel mechanic jobs were posted on the career site Indeed.com.

“There are a certain percentage of students who will not continue an academic education after high school,” said Bruce Stockton, president of Stockton Solutions and a former fleet maintenance executive for national truckload carriers.

He believes carriers need to reach out more aggressively to high schools and vocational schools, invite students to open houses and shop tours, and position the opportunity as a career with many paths for upward mobility.

High schools represent a candidate pool ripe for aggressive recruitment.

Universal Technical Institute, for example, earlier this year launched “Ignite,” a free summer program targeted to high school juniors that lets them “test drive” a technical education. The curriculum emphasizes the high-tech nature of today’s transportation industry.

The program’s two three-week courses give participants hands-on training, providing a foundation in fundamental transportation technician skills, and “a taste for the fulfilling career opportunities that await in the transportation field,” UTI CEO Kim McWaters said. The “Ignite” program will be offered at each of UTI’s 12 campuses nationwide this summer.

Another provider of vocational and technical training is West Orange, N.J.-based Lincoln Tech. Started in Nashville, Tenn., in 1946, where it still has a diesel tech campus, the company operates diesel technician training schools in six U.S. cities. Programs are led by ASE (Automotive Service Excellence) certified instructors. Several of the campuses are backed by partnerships with companies such as Hot Rod and NAPA. Potential employers partner with Lincoln Tech to hold regular recruiting fairs at campuses where graduates can learn about job opportunities with some of the nation’s largest fleets and manufacturers.

In this high-demand environment, all the time and effort spent on recruiting, training and hiring can go for naught if the newly minted technician leaves.

“Retaining what you have is critical as well,” said Steve Studer, senior manager of fleet services for CFI, a truckload carrier based in Joplin, Mo.

That starts with respect, trust and recognition.

Strong internal promotion programs, career pathing, mentorship, transparent interviewing and an open-door policy that welcomes technician input are all key. “Our management team has weekly meetings with all the techs to make sure they have what the need to be successful, and to hear their ideas for improvement,” Studer said. “It’s important to show each tech how they are contributing to the company’s success.”

For CFI, that has the dual benefit of building a strong bond with the employee and strengthening the company’s image as a go-to employer.

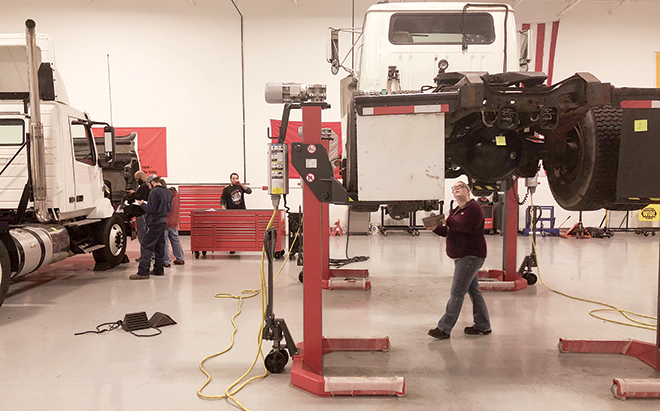

A training class in session at the TA and Petro Stopping Centers Training Center in Lodi, Ohio. (Travel Centers of America)

Chad Estle, lead truck services recruiter for TravelCenters of America, notes that he’s competing with other high-demand trades in recruiting potential technicians, a challenge made that much tougher by low unemployment. TA needs technicians to staff a 24-7-365 operation, which adds another wrinkle. However, he’s undeterred.

“We offer one of the top tuition reimbursement programs in the industry,” he said. Another element: “Work with them to provide a growth path for certifications, participation in competitions and a path to management.”

How have the skill requirements changed, and what are institutions doing to address the need?

“Modern technicians face an incredible challenge,” said Mark De Lima Jr., a field service trainer for TA. “Truck components and controls used to consist of a switch, a load, a ground, some wire and some protection devices,” he said, noting that now they're electronic networks of data links, field effect transistors and multiple controllers.

Skills needed to diagnose and repair these systems have evolved considerably and will continue to do so as more connected devices and other electronic assist-and-control systems come into use, such as all-electric powertrains and self-driving truck technology.

“Technicians that once counted on their trusted test light must now learn to use picoscopes and understand the displayed waveforms,” De Lima said. “In the near future, using a scope to check an electronic control system will be as common as a digital multimeter.”

Many companies are thinking creatively about how to solve the recruiting and training dilemma.

Daimler Trucks North America, the manufacturer of Freightliner and Western Star trucks, offers two training programs designed to nurture and produce entry level technicians: Finish First and Get Ahead. Finish First is a 12-week hands-on training program offered at UTI’s Arizona and Illinois locations. Get Ahead is a partnership program among Daimler Trucks North America, diesel schools and DTNA service network locations. The truck maker has 154 schools enrolled in the program in the United States and Canada. All schools are sponsored by a Freightliner dealer or Detroit distributor.

Jerry Swanson, principal at Freightliner dealer Empire Truck Sales in Jackson, Miss., advocates for more industry-college partnerships. He was an early driver of the Get Ahead program. He also took the initiative with local Hines Junior College to establish a four-semester program designed to turn out qualified entry-level diesel technicians, who upon graduation can start with dealers in apprenticeship positions.

The Hines JC program consists of four eight-week semesters. The first two cover basic theory on subjects such as electricity, hydraulics and other foundational systems, along with basic math and English. The second two move into more specialized and hands-on training around computer and diagnostic systems, electronic controls, truck operating systems and technologies, troubleshooting processes, techniques and other skills.

“Whoever wins the service game and keeps the customer on the road is going to be the real winner,” Swanson said. “And we want to be that winner.”